Why Taxation Matters

Taxes fund the services we all depend on. Without them, governments become asset-poor and unable to protect the most vulnerable in society. There is no such thing as a perfect tax system, but some taxes are more progressive than others. A fairer tax system supports equal opportunity & unequal outcomes, which are the foundations of real social mobility.

Progressive vs. Regressive

Progressive taxation asks people who have a bit more to pay a bit more but can be controversial when they apply to work over wealth and when services dont improve. Regressive taxes tend to fall hardest on low-income households.

Protecting the Vulnerable

A state with no assets cannot rescue those most in need during crises, whether housing, health, or climate emergencies.

Social Mobility

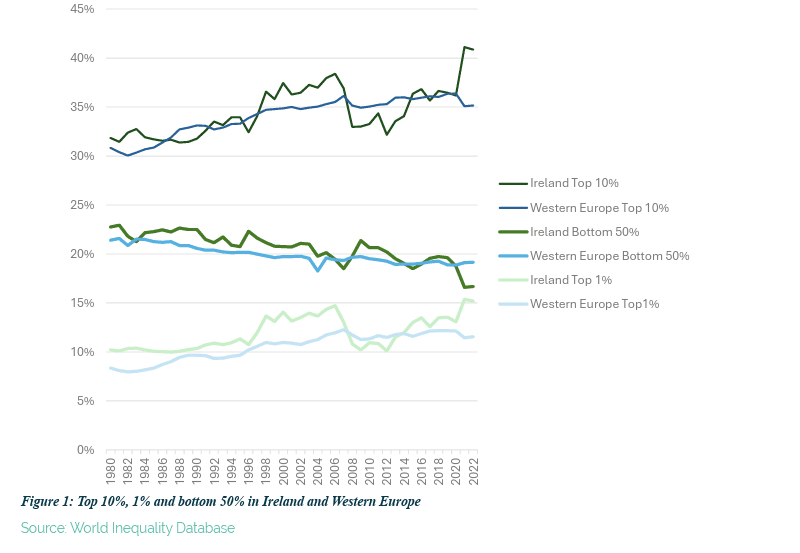

Ireland’s inequality is lower than in the UK or US, partly thanks to tax policy which raise funds from those with the deepest pockets, although more attention should be paid to extreme wealth, infrastructure and corporate loopholes.

Fair taxation doesn’t aim to equalize outcomes—it ensures a fair start in life. When designed well, it gives young people access to housing, healthcare, and education without leaving families solely dependent on inheritance or luck.

Why wealth distribution matters

There is only a certain amount of wealth in a country at any given time. We know that growing wealth concentration is in fact a natural tendency of capitalism over time. This means that over time, the natural course of events is for a higher share of nations wealth to end up in the hands of fewer people. A lot of attention is paid to the unfairness of redistributing any money away from the extremely wealthy. But if a society has no redistributive efforts, the redistribution will still happen, just the other way. Nobody likes paying taxes. But moderate taxation can redistribute wealth more fairly and fund social services, reduce rising wealth gaps, and promote greater economic equity in society. Therefore, if taxation can address the high levels of concentration in the digital industry, then it will likely serve as a useful tool to stimulate a more equal, innovative, and prosperous society.

A poorly designed system, however, erodes fairness and fuels economic unfairness—where effort no longer matches reward. This creates the conditions for political instability and falling social mobility.

The challenge is not to design a “perfect” system, but to design one that minimizes harm and maximizes fairness. Taxes should work for the majority, not just the wealthy few. In developed societies, unfairness exists where there is too much focus on the maximisation of wealth.

Conversely, in some places like parts of Latin America aggressive redistribution to enforce equal outcomes has created situations in which reward does not depend on effort anymore. However, when it comes to quality of life, radical individualism and reliance on market solutions alone will always fall short. Problems like healthcare, education, infrastructure, and climate change are too complex and interconnected for any one person — or even the free market — to solve by itself. That’s why societies build public institutions: so that when everyone contributes a little, we can create services and systems that benefit us all.

The key is accountability — ensuring these institutions are transparent and effective, so people continue to trust in collective cooperation as the best path to improving lives. With a robust and strong public infrastructure in place, enterprise and the market can step in and innovate, creating competitive and productive societies built on a solid foundation.

Wealth, Pandemic Profits & the Case for a Solidarity Tax

A Reuters analysis found that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the share of global household wealth held by billionaires rose sharply — from just over 2% to around 3.5%. This growing concentration of wealth not only widened income gaps but also contributed to higher asset prices, including housing. When wealth compounds at the top during crises, capital flows increasingly toward property and investment assets, driving up house prices and making affordability worse for ordinary people. (Source: Reuters)

In Ireland, a former Minister for Social Integration floated the idea of a one-off solidarity tax on those who benefited most from the pandemic — individuals and tech corporations that saw exceptional profits while others struggled. The proposal, covered by RTÉ News, asked whether those least affected by lockdowns should contribute more to help rebuild public services and social supports.

According to the Minister, such a tax could provide a very real and tangible economic mechanism that could help offset the potential of the pandemic to deepen inequality

The idea was not about punishment but fair contribution. A temporary solidarity levy could help reclaim part of the extraordinary gains made during the crisis and channel them toward rebuilding essential public assets — healthcare, education, housing, and climate resilience. While not a permanent fix, such measures can promote fairness, reduce wealth distortions, and strengthen public trust in collective solutions.

Click to Expand

Edna Krabappel on Fair Funding

In this clip, Edna asks for a modest cost-of-living adjustment to fund extra school books. Instead of support, she is shouted down—a parody of what underfunded teachers face in real life.

While the income tax system is highly progressive, taxation of big wealth in Ireland is low by international standards. Measures such as marginal 1-5% tax rises on the extreme wealth (e.g over 12 million) and our biggest polluters can prompt more fluidity in the housing market and help course correct this gradual transfer of assets to the super rich that has been happening in much of the developed world over the last few decades, and this is good for social mobility.Social Mobility

Social mobility refers to the ability of individuals or families to move up or down the social or economic ladder — for example, improving one’s income, education, or living conditions over generations. High social mobility means a fairer society where effort and opportunity, not background, are primary markers of success.

Equal Opportunity & Unequal Outcomes

Biological evolution gave humans a fairness instinct, and cultural evolution has elevated fairness as a core value in developed societies. Fairness enables complex cooperation — the foundation for economic growth and rising living standards.

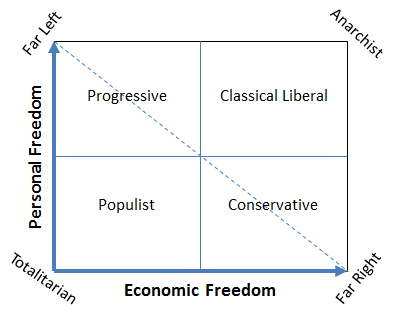

Everyone holds their own idea of what constitutes fairness or unfairness. Within our political systems, multiple ideologies compete to give voice to these instincts. Populism is one such ideology — a movement that claims to defend the interests of the common people against a perceived elite. Its language is steeped in fairness: it’s anti-elite and channels frustration toward those accused of “rigging” society in their favour.

Some inequality is necessary for a healthy, competitive society where effort and innovation are rewarded. This is the principle that underpins capitalism and distinguishes it from communism. Economic unfairness, however, arises when people believe that their input no longer matches their reward — especially when compared to others. For these feelings to matter politically, they must be widespread and persistent. Since the 1990s, they increasingly have been.

This sense of unfairness explains the resonance of slogans like “Make America Great Again,” “Au Nom du Peuple,”and “Take Back Control.” Populist figures succeed by appealing to “forgotten people” living in a “rigged system.”

— Reclaiming Populism, 2021

Social Mobility: The Hidden Measure of Fairness

Social mobility measures how much a person’s life outcome depends on their parents’ wealth. In low-mobility societies, it’s hard to get ahead without being born into privilege — a clear violation of “economic fairness.” In high-mobility societies, success depends more on merit and opportunity, leading to fairer outcomes overall.

Ireland has historically enjoyed relatively high social mobility. However, the ongoing housing supply crisis coupled with the unrelenting rise in asset/house prices threatens to erode it. When hardworking people cannot afford a basic necessity like shelter, alarm bells should ring. As one Irish party leader recently noted, Irish millennials are on track to be the first generation worse off than their parents — a claim supported by both data and lived experience.

Home ownership rates have collapsed. Institutional investors dominate the rental market, trapping many people between unaffordable rents and unreachable mortgages. This is falling social mobility in action — and it’s one of the key conditions that allow populism and anti-democratic sentiment to grow.

The Core of the Problem

Academic research and real-world data point to economic unfairness as the single most convincing explanation for the populist wave across the developed world. The problem is not primarily racism, immigration, or envy — it’s the everyday experience that no matter how hard one works, the system is stacked to favour someone else.

Populists have thrived because they connect with those who feel voiceless and locked out of opportunity. Their message resonates not because of ideology, but because of experience — a sense that society has stopped rewarding fairness, and that the economic game itself has been rewritten.

Source: The Irish Times, 2022

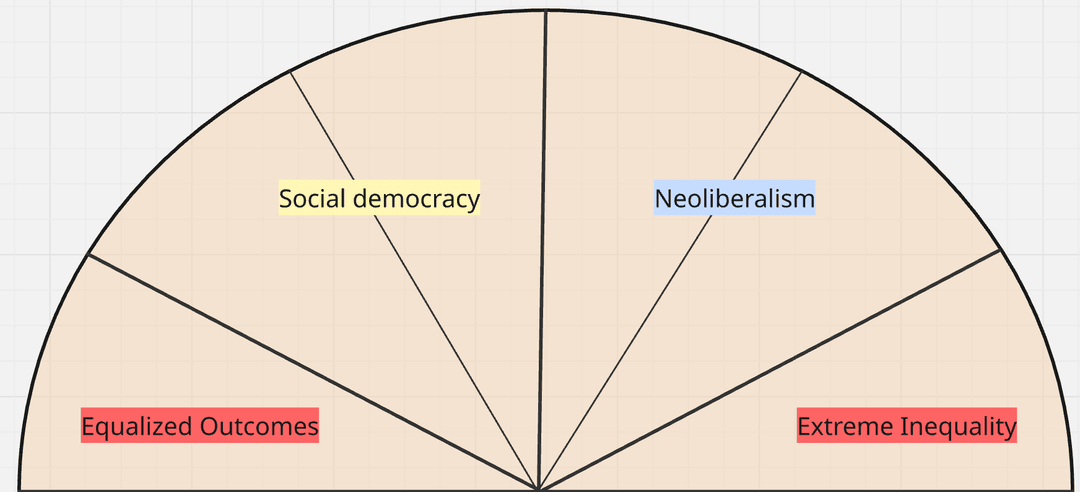

Economic Model Examples

Note: Ireland is often considered a mixed-market economy with a neoliberal tilt.

Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism is an economic philosophy that emphasises free markets, individual competition, and minimal government intervention in the economy. It became dominant in Western democracies from the 1980s onwards, promoting privatisation, deregulation, and lower taxes for high earners. Critics argue that it concentrates wealth, weakens public services, and reduces democratic control over essential resources. Proponents argue that it stimulates innovation, investment and job creation.

Social Democracy

Social Democracy is a political and economic model that combines the efficiency of markets with strong social protections and democratic oversight. It supports private enterprise and trade but emphasises government responsibility for ensuring social welfare, public healthcare, education, and workers’ rights. Originating in Europe, it seeks to balance capitalism with fairness and equality through progressive taxation and redistributive policies. Advocates argue that it promotes stability, opportunity, and shared prosperity, while critics claim it can lead to overregulation and reduced economic dynamism.

Mixed-Market Economy

A Mixed-Market Economy blends elements of both capitalism and government intervention. In such systems, most businesses are privately owned, but the state plays a key role in regulating markets, correcting inequalities, and providing essential public services. This approach aims to harness the innovation and efficiency of private enterprise while ensuring that economic growth benefits society as a whole. Supporters view it as a pragmatic balance between freedom and fairness; critics argue that it can result in bureaucratic inefficiency and blurred lines of accountability.

Well-being Economy

A well-being economy is an economic system designed to prioritize human and ecological well-being over traditional measures like Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth. It shifts the focus to ensuring everyone can live with dignity, safety, and purpose within the planets sustainable limits, emphasizing social justice, fairness, and a healthy environment as central goals.

5 Tickets for Better Social Mobility

Adopt dedicated wealth tax on super-wealth in excess of 12 million euros.

SDG 10Additional property tax on vacant residences & higher stamp duty on vulture funds.

SDG 10Weight-based tax on heavy vehicles to cut energy use & improve public health and road safety.

SDG 3SDG 13Advance Sláintecare & improve working conditions for medical workers.

SDG 3SDG 8Increase investment in disability services, public infrastructure such as childcare, teen community centres, public transport & state-built, transport oriented housing.

SDG 1SDG 3SDG 4SDG 9SDG 11